The Board is Set

The Norman invasion of 1066 not only changed the course of English history forever, it would shape the future of France for centuries to come as well. The new English aristocracy formed under the feudal Franco-Norman conquerors ensured far reaching territorial claims on both sides of the English Channel. Roughly half of modern France's western territory would eventually come under their sway along with the formerly Saxon ruled Kingdom. These holdings would go on to be disputed by King Philip VI's Great Council in Paris in 1337 as they found their grip on the tacit vassalage of England slipping along with their influence on the continent. This would culminate in the virtually inevitable conflict known as the Hundred Years' War.

The Pieces Move

By 1346, the War had been raging for nearly a decade with no clear resolution in sight. King Edward III of England engaged in three costly and inconclusive campaigns in Northern France at this time followed by a fourth attempt in 1345 foiled by foul weather effectively scattering his invasion fleet. Undeterred, Edward began raising a fresh army of his vassals and a new fleet of 700 vessels, the largest assembled by the English up to that point. On July 12, 1346, the fleet landed at Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, Normandy. Given the speed with which this new force was raised following the former's floundering, the English were able to achieve total strategic surprise. This allowed for the smooth debarkation of their forces and relatively light opposition as they marched south, razing and looting every town in their path. On August 24th, the English army defeated a French force defending the Somme and subsequently forded the river following the enemy's rout. King Edward would march his army to lands inherited from his mother, Crécy-en-Ponthieu–long considered a prime defensible locale well suited to a battle–and dug in.

The Army of King Edward III of England

Contemporary accounts of the size of the English army vary wildly from 7,000-15,000. As is typically the case, the truth likely lies somewhere in the middle. What we do know is that there were somewhere around 2,500 men-at-arms at Crécy, all fighting dismounted. This core body of the army was augmented on foot by a large contingent of highly proficient English and Welsh longbowmen, probably around 5,000 strong, and several thousand levied infantry and militia armed with polearms. Mounted support came in the way of a few thousand hobelars, light cavalry originating in Ireland. Evidence for primitive artillery has been found at or near the site of the battlefield adding credence to period reports of so called "organ guns" and bombards formed in the English vanguard, though what level of effect these machines had on the outcome of the engagement is unknown.

The Army of King Philip VI of France

Even less is known regarding the exact size and composition of the French forces beyond primary sources of the time, seeming to agree that the levied infantry spearmen alone outnumbered the entirety of the English army. Modern estimates of the total force based on French financial records from 1340 related to raising a similar force and contemporary accounts of the battle indicate a likely composition of around 8,000 mounted men-at-arms, roughly 12,000 infantry and 5,000-6,000 hired Italian crossbowmen primarily from Genoa. This gives us a large potential army of around 25,000 men.

The Deployments

The English army arrived prior to the French allowing them to choose their ground. King Edward divided his army into three battalions, known as "battles," each with a core block of men-at-arms and infantry flanked by longbowmen in open skirmish order. They took position at the top of a slope in the land between the village of Wadicourt securing its left flank and Crécy its right. The archers dug pits up the face of the slope in order to hamper French cavalry movement.

Edward's hope for victory lay in goading the French into a charge up the hill and through the ditches into his massed blocks of lances and spears allowing the Longbowmen time to lose as many bodkin point arrows as possible. Though the longbow can accurately lose up to 10 arrows a minute over 300 yards in skilled hands, the Welsh bowmen intended to wait until the plate armored mounted men-at-arms were within 80 to begin their massed vollies to ensure maximum penetration of their opponent's defenses.

French scouts reported the English army's position to their officers and a war council was promptly convened. Perhaps due to being overwhelmingly confident of an assured victory given their superior numbers, and despite having marched for several hours, King Philip ordered the attack on Edward's army to commence that very afternoon on August 26 1347. Their order of battle differed greatly from the dug-in English. Italian crossbowmen exclusively comprised the French vanguard resulting in an archery duel with the Welsh and English longbowmen. Despite greater draw weights and penetration power at shorter ranges, the crossbow's overall range fell roughly 100 yards short of the bow. This, coupled with the slower reload time of about two shots per minute for a trained man and the muddy conditions of the field, resulted in a paltry effort on the part of the Genoese before they fled the field with light casualties. By some accounts, many Italians were cut down by the advancing French troops.

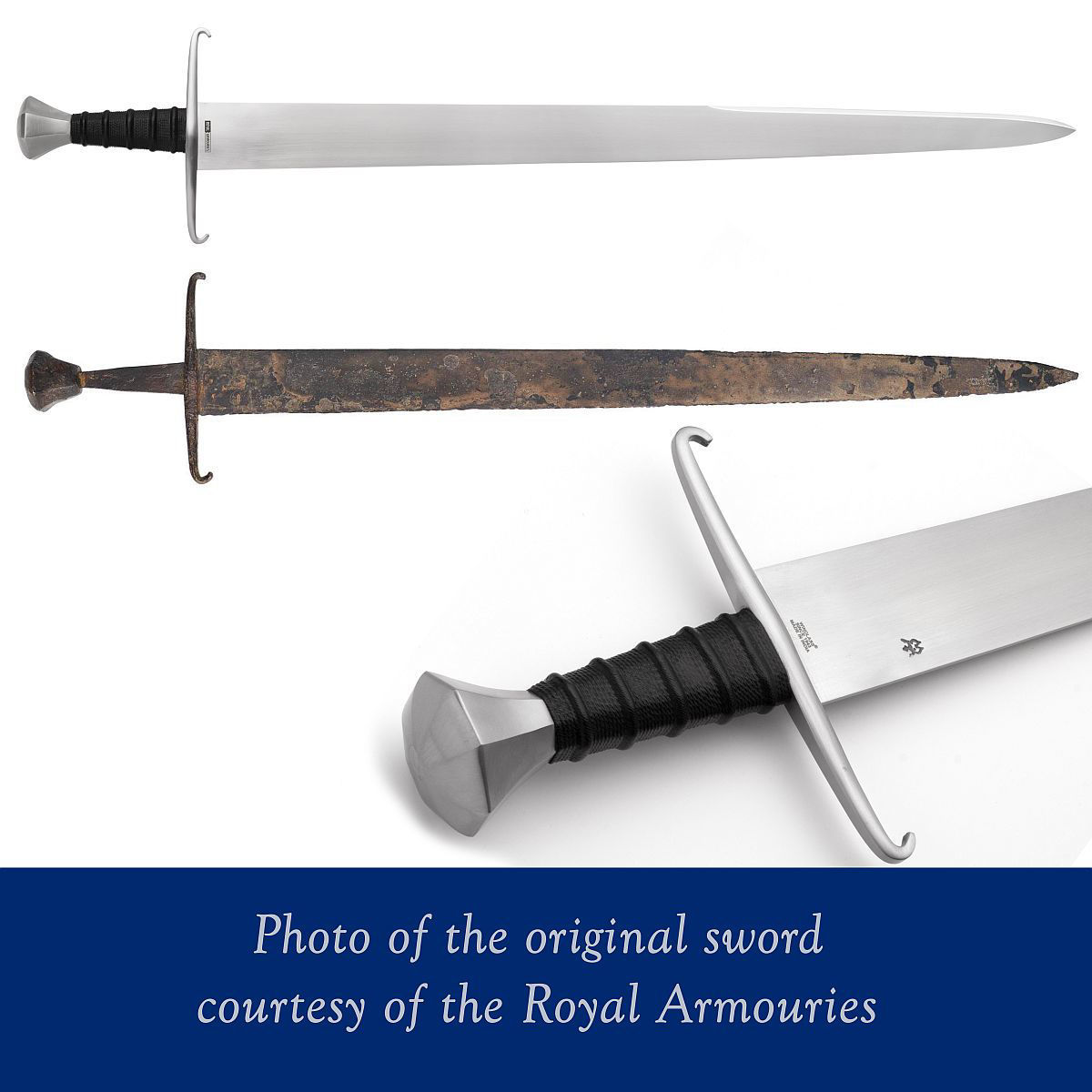

As the French Knights waded their way through the fleeing Italians and the mud, they began a disorganized and impromptu charge up the hill. Hampered by the pits and ditches dug by the archers prior to the battle, their slow advance allowed for several devastating vollies to be loosed upon them before crashing into the English infantry lines for brutal and nightmarish close combat described by a contemporary source as "murderous, without pity, cruel, and very horrible." French knights who were dismounted and infantrymen who lost their footing were crushed under falling masses of dead horses and men. The first charge had been repulsed.

The Victors

The French reformed their line in a disorderly fashion at the bottom of the hill following their hasty retreat. Still in range of the longbowmen, they haphazardly attempted another charge up the increasingly treacherous hill now heavily obstructed by the fallen. The Prince of Wales, while leading the English vanguard, was reportedly "beaten to his knees" in the carnage of the second charge. His standard bearer beside him is said to have stood on the banner to prevent its capture. Again the French were repulsed. This cycle would repeat late into the night, becoming more and more gruesome and disorganized until finally, after losing two horses from under him and receiving an English arrow in the jaw, King Philip VI of France fled the field.

- Written by Lord Wallis the Weird