The evolution of the political system in ancient Greece was closely mimicked by the evolution of war itself. When most people think of ancient Greece they think of their philosophy, theater, democracy, the hoplite soldier and so on. What most don't realize, however, is this view of ancient Greece only applies to a certain period: the Classical Age of Greece. The Classical Age is when Greek influence truly began to spread along with Greek culture. Greek warfare became focused around the hoplite and phalanx formation. Athens dominated the sea with their navy and Sparta dominated the land with their unstoppable army.

Before this age could develop, however, Greece went through the Archaic Age. This is the age of heroes and kings. Battles were hundreds or thousands of individual duels and nobles became known throughout the land for their battle prowess. Achilles and Hector, Ajax, and Odysseus were all heroes of the Archaic Age where they gained great prestige through their skill in battle or cunning and intelligence. There was no such thing as democracy. Kings and nobles ruled. As only the kings and nobles could afford the best armor and have the leisure time to train, it was these men that stood out in war. All things change with time though. A new kind of soldier and warfare emerged that would dramatically alter the course of Greek history and, arguably, the world. Marble Bust of Odysseus, 2nd c BC

The hoplite developed as the common soldier and helped usher in the Classical Age of Greece. A hero of ancient Greece may be powerful but a wall of men, each protecting each other with their shields, could present a great warrior with no opening to attack. Over time, the method of war composed of noble duels and nameless grunts gave way to the hoplite and phalanx. During battle, each man in a phalanx was equally prepared to give his life and face the dangers of war to protect his family and home. As a result of this, each man began to see himself as equal outside of war as well. Nobles and kings could no longer claim the glory as they no longer contributed to battles. The common man grew in status and equality and over time, the concept of democracy was born.

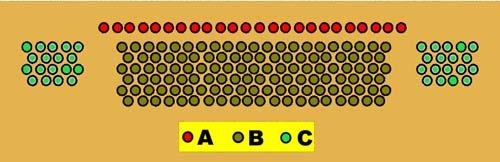

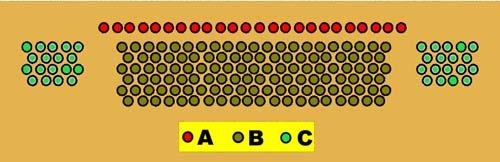

Not only was the phalanx and armored hoplite able to defend Greece from Persian invasions, but, with the development of democracy and more equal status to everyone (at least to free men who owned property), the culture of Greece was able to bloom and prosper along with the cities of Greece. Sparta, however, was left behind in this bloom of culture. Ever traditional, Spartan law forbade all Spartan males from any profession other than that of war. This enabled Sparta to become incredibly powerful and influential on the field of battle and in Greek politics for a while but left them severely lacking in any developments of culture. As time went on and tactics evolved along with technology, Sparta's rigid structure became its downfall. Once it no longer had the military power to dominate Greece, its influence drastically fell and, eventually, so did the city itself. Ancient Greek phalanx formation A. Peltasts B. Hoplites C. Cavalry

The phalanx was the most powerful fighting formation in the world for several hundred years. When Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great upgraded and rearranged the phalanx it was able to help bring down the largest ancient civilization in existence, Persia. This opened up both Greece and the Middle East to each other and much of the known world, forever altering the cultures and civilizations of the peoples affected. Just like Sparta's rigidness, however, the phalanx's lack of ability to adapt became its downfall. Like much of the Mediterranean world, Greece was eventually conquered by the Romans whose highly flexible and adaptable battle formations defeated the rigid Greek formations. Greek culture, however, was so influential and advanced that the Romans incorporated most of it into their own culture and civilization. Over a thousand years later, Greek and Roman culture became the catalyst that propelled Europe out of the Dark Ages and into the Renaissance. by Alex Smith, MRL staff writer